Purposeful rounding is a proactive, systematic, nurse-driven, evidence-based intervention that helps us anticipate and address patient needs. When applied to nursing, rounding often is described as “hourly” or “purposeful.” We prefer the latter term, because on some units or at certain times of day, rounding doesn’t take place at hourly intervals.

As we travel around the country and interact with nursing staff and leaders in units and organizations of all sizes, we often encounter nurses’ frustration with purposeful rounding. It’s not that they don’t believe in it; rather, they don’t know how to get purposeful rounding to “stick” because it entails asking staff to reorganize and approach their work in a completely new way to accommodate the rounding schedule. Some caregivers have been organizing their shift the same way for more than 30 years. Rounding forces nurses to change their habits—and as

we all know, changing habits is hard. If we expect them to make this change, we have to present them with extremely compelling evidence that rounding works.

Fortunately, the evidence is compelling. A growing body of research suggests effective purposeful rounding can promote patient safety, encourage team communication, and improve staff ability to provide efficient patient care.

Purpose and intent

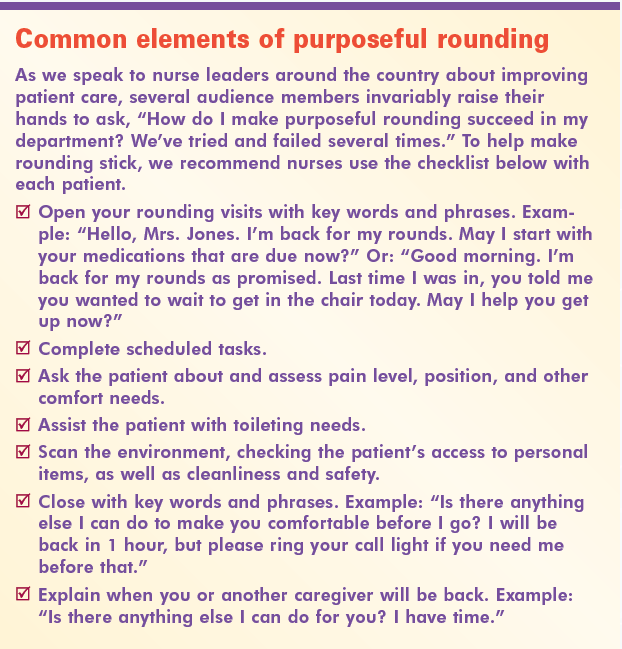

Purpose and intent—the forces that make rounding effective—go beyond quickly eyeballing the patient and asking “How are you doing?”, followed by a hasty checkmark on a whiteboard or rounding sheet. Purposeful rounding with intent is a work process that structures the time staff spends with the patient by using an actual or mental checklist of procedures meant to promote optimal outcomes in a clean, comfortable, safe environment. (See Common elements of purposeful rounding.)

Making rounding a common practice

The systematic process of rounding is an intentional act conducted with clear purpose for the patient’s benefit. It has significant value for the patient. In light of its value, how can we make it common practice on nursing units?

One way is to organize rounding as a process-improvement initiative. It’s not enough to simply write a new policy, create a new documentation process, and run it by staff at the next department meeting. To succeed, purposeful rounding must be implemented through a formal change-management process, such as the Plan-Do-Study-Adjust cycle.

Also, the change process must involve staff, not just leaders. Recently, a large tertiary-care hospital asked our company to reimplement purposeful rounding 2 years after its initial attempt failed. When we went on-site to meet with the team responsible for reimplementation, we saw it consisted solely of leaders (as it had 2 years earlier). But rounding requires a change in the work of staff, not leaders. Our advice to these leaders: “Do it with staff, not to staff.”

As the process improvement proceeds, the organization should evaluate options related to technology’s role. Emerging technologies similar to call-light systems can assist the new workflow by alerting caregivers when rounding is due. They also can simplify documentation, monitoring, and reporting. Yet while such technologies exist, we’ve also seen successful implementation that didn’t involve technology.

Approaches to purposeful rounding

The implementation team also needs to grapple with how to customize purposeful rounding to each unit. For instance, they need to consider how purposeful rounding will meld with the organization’s nursing model. To accomplish purposeful rounding, facilities can take one of three approaches: primary, team, and functional. (For a description of these approaches, see the online version of this article.) The team must determine which approach would work best for each unit, develop a checklist of tasks to perform during purposeful rounding, and determine rounding frequency.

Implementing rounding

Once planning is complete, implementation can take place. However, we’ve often seen change efforts stop at this step. In units that need to tackle multiple improvements or changes, the “Plan-Do” steps for one project may be followed quickly by the “Plan-Do” steps for the next. For the best chance of success in process improvement, each change must be followed by “Study” and “Adjust” activities. The team must make sure to study even the best-planned changes to determine if they’re accomplishing their aim and if each change has taken hold. In many cases, adjustments are needed.

Don’t skimp on the step of validating that the change really is happening. With purposeful rounding, validation can be both subjective and objective. Subjectively, a leader can round on some or all patients in the unit daily; we call this validation rounding. Say to the patient, “I want to make sure that when you need anything at all, your call light is being answered promptly. Is this happening for you?” It’s music to the leader’s ears when the patient says, “Actually, I never have to ring my call light. My nurse is always right here when I need her.”

When following up on findings from validation rounding, leaders can seek out the caregiver assigned to the patient to recognize her or him for purposeful rounding. Or, in some cases, the leader may need to ask, “What’s getting in your way of purposeful rounding with every patient every hour?” Some of the best ideas for adjustments to rounding can come from conversations between leaders and caregivers.

For objective validation, use data. Are call-light volumes going down? What’s happening to patient satisfaction scores for such items as pain and responsiveness of staff? What trends do you see in your unit’s patient falls and pressure ulcer rates?

Call to action

For our patients’ sake, we need to get beyond our frustrations with purposeful rounding efforts and beyond the perception that rounding is just another daily task in a seemingly endless list. Remember—purposeful rounding is purposeful work. Patients aren’t interruptions in our work; they are our work. Purposeful rounding is a proactive strategy that helps us manage our work.

A formal process-improvement initiative driven by frontline caregivers is the vehicle that makes purposeful rounding happen—and makes it stick. If you’ve tried it and it’s not working, try again. If you’re about to make that first attempt, just start.

Selected references

Halm MA. Hourly rounds: what does the evidence indicate? Am J Crit Care. 2009;18(6):581-4.

Meade CM, Bursell AL, Ketelsen L. Effects of nursing rounds: on patients’ call light use, satisfaction, and safety. Am J Nurs. 2006;106(9):58-70.

Jane McLeod and Sue Tetzlaff are cofounders of Capstone Leadership Solutions, Inc., in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan.

4 Comments.

what are the findings of purposeful rounding in skilled nursing facilities. With the number of residents a staff is caring for, does this seem reasonable. I think it is a great plan, however how does it work in SNF with the number of residents one staff member is caring for.

aaaaaaaaaaaa

I like the purposeful rounding I like the idea I’m like the concept I do it without actually doing it I guess you could say I’m a CNA so I can offer the medication but what I do offer them is what can be done are they need to talk with a lot of them need to are water some more ice a snack if it’s before or after a meal but majority of the time they just want to talk the last place I worked at they had three rounding sheets of paper to remind people to check and change water and so on I mean when you become a CNA are you become a nurse and working in a care home you already know that you need to check them to see if they’re thirsty are if they’re uncomfortable change them out of the brief or if they’re hungry offered to bring them something it’s their home

I love this phrase ‘ purposeful rounding’. We call it hourly rounding ours do not sound interesting like what I have just read now. Having a list of things one would like to accomplish with the patient in getting to his or room will make it more efficient, than just walking in to the patient’s room to just ask how are you? or are you in any pain.