Editor’s note: This article is the first in a three-part series brought to you in partnership with the International Safety Center. Watch for the next two articles on blood and body fluid splashes and use of personal protective equipment, respectively.

Since 1992, hospitals and healthcare facilities throughout the United States and the world have used the Exposure Prevention Information Network (EPINet®) as a tool to survey and measure occupational exposures to blood and body fluids. This network is designed to help you and your facility identify safer devices, safer practices, and innovative approaches to reducing occupational exposures to blood and body fluids. EPINet helps identify where infectious exposures are occurring in U.S. hospitals and allows you to compare them to what’s happening in your facility. The International Safety Center distributes EPINet free to hospitals to measure occupational exposures to blood and body fluid that cause illness and infection in the working population.

High-risk injuries from contaminated sharps and exposures, such as mucocutaneous splashes and splatters, pose an unparalleled risk to nurses. Infectious threats, such as Ebola virus, measles reemergence, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), require us to keep an ever-steady focus on surveying and measuring risk so we can mitigate and prevent it. EPINet allows us to do that.

Nurse injuries from sharp objects and needlesticks

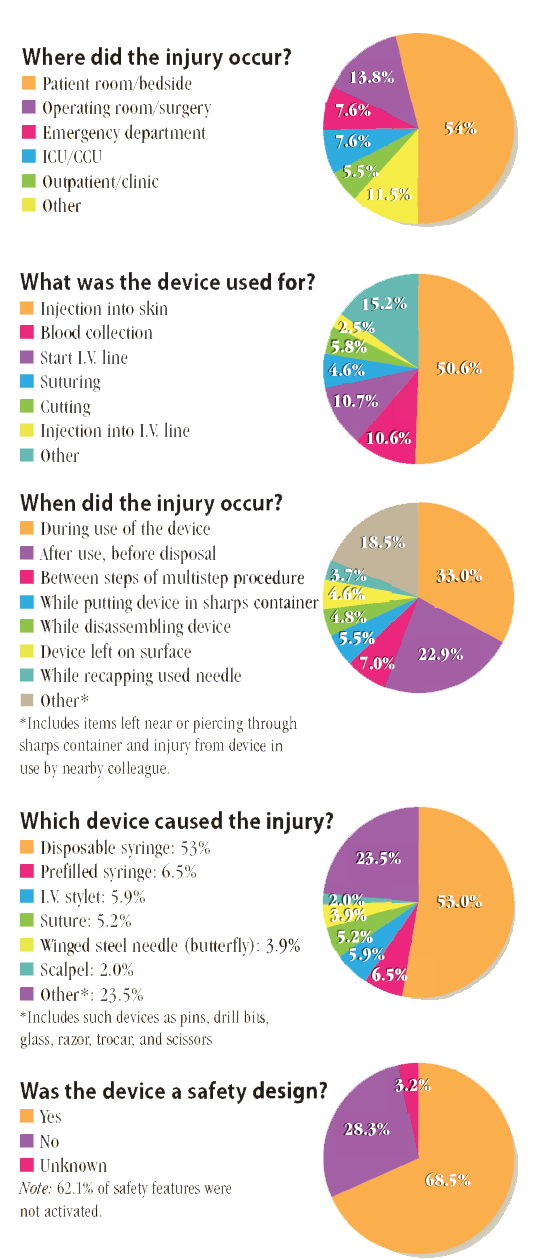

For all sharps injuries occurring across all hospitals, 40.1% happen to nurses. The following statistics are from the most recent EPINet data (the 5-year period from 2009 to 2013).

Protecting nurses

Now that you know the facts, you can take steps to help eliminate needlestick injuries and encourage your employer to take action.

Innovation

Nurses are creative, resourceful innovators. You can directly and positively affect your own life and the lives of your patients and colleagues. If you don’t consider yourself an innovator, look to those you think are. Use such resources as “Nurses leading through innovation” at www.theamericannurse.org/index.php/2012/06/06/nurses-leading-through-innovation/.

The authors work at the International Safety Center (InternationalSafetyCenter.org). Amber Hogan Mitchell is president and executive director. Ginger B. Parker is vice president and chief information officer.

1 Comment.

The article Preventing Needlesticks and Sharps Injuries by Mitchell and Parker (10(5), September 2015) raises a number of important issues. One of these is the use of a device with a so-called “safety design”. Such designs typically offer some means to cover the sharp after use, but the means of achieving that covering vary, as does the associated ease of use. Therefore across the range of designs some may be much better than others at achieving real world safety.

If we look at the data of “Was the device a safety design?” we see that about 64% of injuries occurred with such designs. We are also told that in about 62% of the instances of ‘safety design used’ the safety feature was not activated. This of course leaves 38% for the instances of injuries occurring even though a safety design was actually used. Both non-use and injuries while using deserve further attention.

Non-use can have a range of explanations from passive disregard for the safety feature to an active assessment that trying to use the safety feature is itself dangerous. For some designs such an assessment may be correct in that the manipulation required to operate the safety feature creates increased exposure to injury arising from the very use of the safety feature. Devices requiring two hands, or for which using two hands is much easier than trying to use one, are ones for which active avoidance may be a reasonable decision.

‘Injury while using’ even more clearly suggests that the design itself is dangerous, most likely as a result of the hand and finger manipulations required to operate it, and the likelihood that those manipulations will themselves lead to injury. These manipulations are also related to the “After use, before disposal” category of when injuries occur. The time interval between the end of use and safe disposal includes for “safety designs” the time between end of use and successful activation of the safety feature. This interval can be strongly effected by the design of the device.

These issues suggest the need for distinguishing between devices that theoretically provide safety and those that actually provide safety in the real world of use by real users. Devices that are not successful reflect unnecessary risk, a false assumption that safety will be achieved, and a waste of money. Thus which device was involved by brand and model is essential information for understanding why sharps injuries occur even when a “safety design” is used.

William A. Hyman

Professor Emeritus of Biomedical Engineering

Texas A&M University