As healthcare providers set and refine their strategies for staying competitive in a value-based delivery and payment system, a sharper understanding of the interplay between inputs and outputs becomes a strategic imperative. Nurse staffing is a key input for acute-care hospitals—key both for its impact on care and its budget prominence. This puts it squarely at the center of hospitals’ efforts to deliver on their value promise.

The relationship between staffing and patient outcomes across quality, safety, and experience domains is appreciated intuitively, if not always precisely understood. The imperative to strike the perfect balance drives considerable interest and research in fine-tuning this understanding. Yet vast scholarship on the topic hasn’t produced a precise staffing formula that will lead predictably to desirable outcomes.

That’s because high-quality nursing care hinges on much more than the number of nurses on the job for a particular patient load. It also depends on multiple under-lying structural and process factors, such as nurses’ skills and education, availability of sufficient supplies and equipment, staff training, facilities, and reliable use of demonstrated best nursing practices—as well as such factors as interprofessional relationships, nurse engagement, and job satisfaction.

To fully understand the impact of staffing levels on patients’ clinical and experience outcomes, we must consider the relationships within and among these variables—something we can do only through data integration and cross-domain analytics.

Value of NDNQI data

In 2014, Press Ganey acquired the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators® (NDNQI®)—the industry gold standard for assessing nursing excellence—from the American Nurses Association. NDNQI national benchmarking data are invaluable for monitoring key nursing-sensitive structure, process, and outcome measures. Similarly, Press Ganey’s vast patient experience database offers critical insight into patients’ perceptions about the effectiveness of hospital operations, clarity of the care team’s communication, and caregivers’ ability to meet patients’ needs.

As with nurse staffing, a growing body of evidence shows associations between patient-experience outcomes and clinical outcomes. Combining NDNQI and patient-

experience data provides unprecedented access to the relationships among key pieces of information. Together, these measures can help nurse leaders identify how performance changes in certain structural and process indicators affect patient safety, experience, and clinical outcomes.

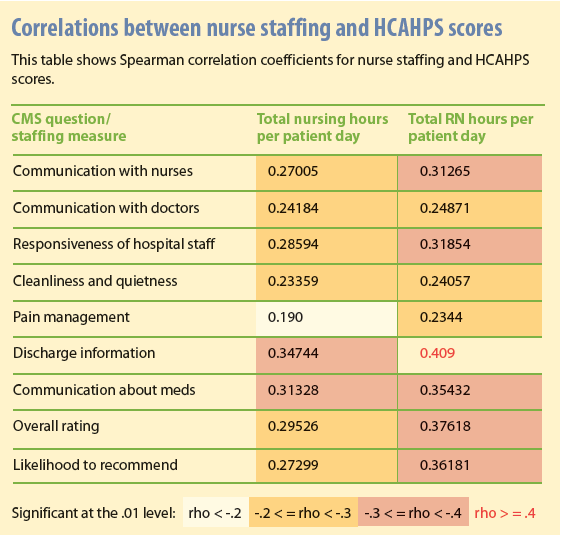

Given the enormous impact of nursing on the patient experience—and because nurse staffing often is a lightning rod in the debate on how to deliver high-value care—using the combined dataset to better understand how the two relate is a research priority. Our early analyses show that performance on both Press Ganey and Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) domains correlates significantly with nursing hours per patient day and RN hours per patient day, with the latter showing stronger associations in every domain. (See Correlations between nurse staffing and HCAHPS scores.) The link between more bedside nurses and a better patient experience isn’t surprising. That the correlations stretch across all experience domains—not just those that examine quality and frequency of nurse-patient interactions—is eye-opening.

Staffing that meets patient needs and reduces suffering

While domain-level correlations confirm long-held beliefs about the relationship between staffing and patient experience, we seek to understand which aspects of the patient experience are most sensitive to staffing. Where do staffing levels make a difference in caregivers’ success in meeting patient needs? Where can staffing serve as a lever to improve performance?

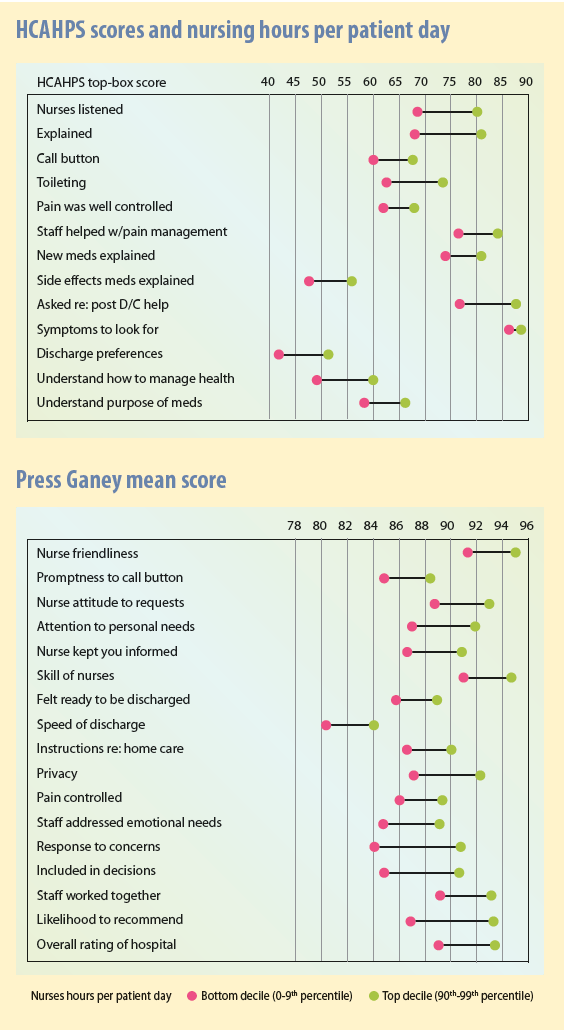

Item- and question-level analyses help answer these questions. In the two tables HCAHPS scores and nursing hours per patient day and Press Ganey mean score, we see that for HCAHPS top-box scores and Press Ganey mean scores, every item showed sensitivity to staffing levels. Where the difference in patient experience scores is greatest (meaning when hospitals in the top decile of staffing ratios dramatically out-perform hospitals in the bottom decile), staffing can be viewed as a more powerful performance-improvement lever.

Reducing patient suffering

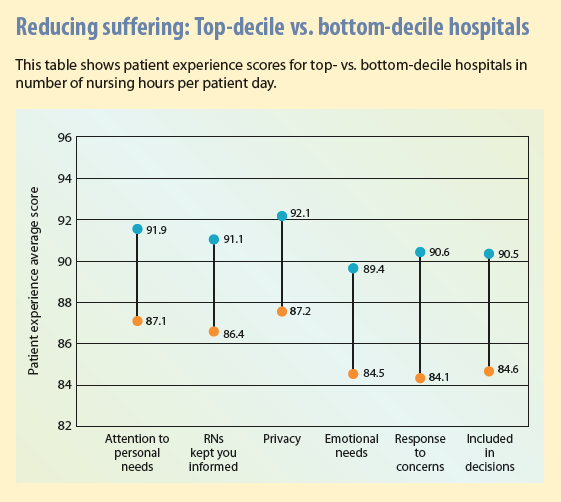

Of particular interest are differences in performance on key patient-experience questions related to patient suffering, which may indicate how effectively an organization provides patient-centered, personalized care. Press Ganey staff believe that relieving suffering should be central to efforts aimed at providing patient-centered care.

Patient suffering falls into two categories:

- Inherent suffering results from the patient’s diagnosis, treatment, or both. It can’t be avoided entirely, but it can be mitigated. Some types of inherent suffering are well understood and addressed with some consistency—for instance, using pain control and explaining and managing symptoms. Inherent suffering includes psychosocial suffering, which caregivers are less comfortable with and therefore less practiced at addressing. Such suffering includes fear, anxiety, confusion, loss of dignity and autonomy, and uncertainty about self-care after discharge.

- Avoidable suffering arises from systemic defects, which may include long waits to receive treatment, poor communication, poor coordination among providers, errors, and failure to follow best practices. An important first step in determining how to avoid that kind of suffering is to understand that dysfunction creates additional suffering for people already burdened by inherent suffering.

Inherent suffering can be reduced by understanding and meeting inherent patient needs. Performance on certain patient-experience survey questions can tell caregivers much about how well they’re meeting patients’ needs. Examining the relationship between staffing ratios and performance on these questions is illuminating. The table Reducing suffering: Top-decile vs. bottom-decile hospitals illustrates the dramatic differences in performance between top-decile and bottom-decile hospitals on questions relating to patient anxiety, autonomy, and the need to be informed about and involved in their care. These differences speak volumes about the importance of adequately resourced nursing units to give caregivers sufficient time to meet these patient needs.

It’s never just one thing

These findings don’t suggest that increasing nurse-patient ratios will automatically lead to performance improvements. Certainly, adequate nurse staffing is key to a range of outcomes, but changing staffing volume alone won’t produce optimal outcomes. Multiple aspects of structure and process also shape outcomes, and these findings must be leveraged with that in mind.

Such factors as demographics of the nursing force, education and certification, engagement, and organizational staffing models are associated with patient-experience outcomes, as are cultural and structural practices and processes. In this regard, answers to the questions below also factor into outcomes:

- Is the nursing staff following best practices associated with better patient experiences?

- Are they executing on those best practices consistently and in the prescribed manner every single time?

- Do nurses have the right resources and training to promote consistency?

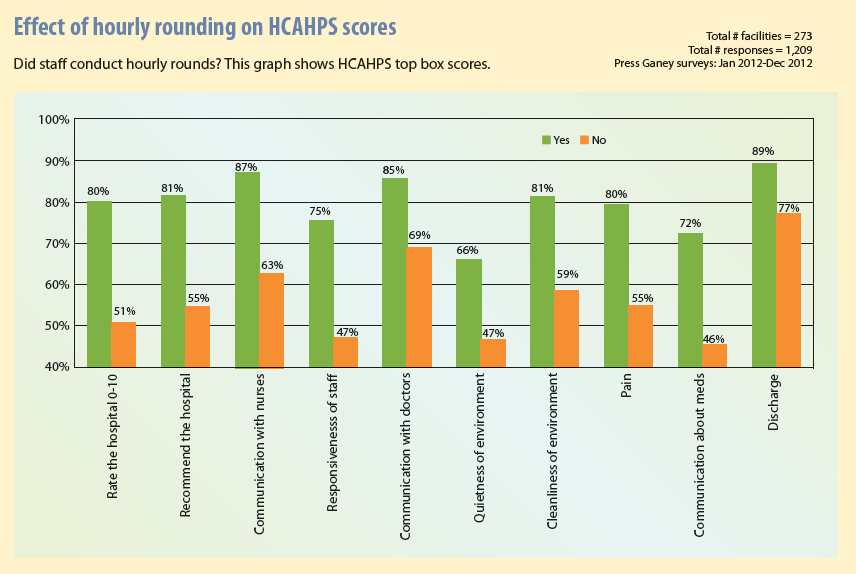

For example, a best practice such as purposeful hourly rounding on patient experience can have a dramatic impact. A 2013 Press Ganey study shows that patients who report they were visited by staff hourly during their hospital stay were much more likely to give top box scores on all HCAHPS questions—a clear sign their needs were being met more consistently. See the table Effect of hourly rounding on HCAHPS scores for details.

The concept of value over volume extends beyond changes to delivery and payment models. For hospitals, “getting it right” with their nursing organizations is particularly important because nursing care provides much of the value hospitals create. Adequate human resources are critical, but they’re not enough on their own. Nurse leaders must consider the full range of inputs—in addition to adequate human resources—that drive outcomes, including staff quality or caliber, the environment in which they operate, and shared commitment to providing a high-value experience for patients.

Nell Buhlman is senior vice president of Clinical and Quality Solutions at Press Ganey Associates in South Bend, Indiana. Note: Charts are copyrighted by Press Ganey and used with permission.

Selected references

Armstrong K, Laschinger H, Wong C. Workplace empowerment and Magnet hospital characteristics as predictors of patient safety climate. J Nurs Care Qual. 2009;24(1):55-62.

Dempsey C, Reilly B, Buhlman N. Improving the patient experience: real-world strategies for engaging nurses. J Nurs Adm. 2014; 44(3):142-51.

Halm MA. Hourly rounds: what does the evidence indicate? Am J Crit Care. 2009;18(6): 581-84.

2 Comments.

My sister wanted to work in a hospital as a nurse and stop being a corporate nurse. It was explained here that people are looking for staff that meets the patient needs and be able to reduce suffering. Furthermore, it’s recommended to go to experts for a trusted RN staffing.

It’s logical that staffing that meets patient needs and reduces suffering. If I were a patient, a lack of staff means a lack of care for me which can increase my pain. The unproportionate ratio of staff to a patient can result to negligence. Thanks for the indulging article! It’s a good food for thought.