Defined as pneumonia that develops within 48 of endotracheal intubation, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is the most common hospital-acquired infection in critical care units. It leads to longer intensive-care stays, increased mechanical ventilation time, greater mortality, and higher costs.

Although VAP incidence in the United States has declined to 0.0 to 4.4 cases per 1,000 patient days, it remains a concern. Prevention strategies focus on three causative mechanisms—bacterial colonization of the respiratory and upper GI tracts, aspiration of contaminated secretions, and contamined respiratory equipment. Understanding evidence-based strategies can help you reduce your patients’ VAP risk.

Recognized evidence-based strategies

Several professional organizations have developed or endorsed evidence-based guidelines for VAP prevention. Here are four of the most commonly recommended strategies.

Use an endotracheal tube with a lumen for continuous suction of subglottic secretions.

Contaminated secretions pool above the endotracheal tube cuff and migrate into the lungs even with a properly inflated cuff. Continuous removal of these secretions by suctioning reduces aspiration risk. Endotracheal tubes with a continuous subglottic suction lumen are linked to re-duced VAP rates and decreased duration of mechanical ventilation in patients who need more than 48 hours of ventilation.

Keep the head of the bed elevated 30 to 45 degrees.

Unless medically contraindicated, keep the head of the bed elevated for patients with a high aspiration risk, including those who are on mechanical ventilation or have an enteral feeding tube. Supine positioning is linked to higher bacterial counts in aspirated secretions than semirecumbent positioning. Use the bed’s angle-indication device to ensure an accurate elevation angle; nurses’ estimates of the angle have been shown to be inaccurate.

Commit to an oral care protocol using chlorhexidine.

Within 48 hours of hospitalization, the oral flora of critically ill patients changes to include potential respiratory pathogens rarely found in healthy persons. The endotracheal tube provides a migration route for organisms to travel to the lungs. Oral hygiene protocols with chlorhexidine help combat colonization of the respiratory tract and reduce dental plaque (which acts as a bacterial reservoir). Although chlorhexidine 0.12% solution is the most commonly used concentration, no firm consensus exists for the most effective concentration. The strongest evidence for chlorhexidine has been reported in the cardiac surgery population, although many hospitals regularly use it for noncardiac surgical patients.

Change the ventilator circuit only when visibly soiled.

Studies evaluating contaminated ventilator circuits show that changing circuits more often doesn’t reduce pneumonia incidence. In fact, changing circuits less often may reduce exposure to infectious aerosols. Before patient repositioning, drain the condensation in circuits away from the patient. For details on disinfecting and sterilizing respiratory equipment, visit www.cdc

.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5303a1.htm.

Other best practices

The practices described below are recommended for VAP by at least one professional organization, although they’re not cited as often as the above interventions.

Use NIPPV to avoid intubation or reintubation.

Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) can be a useful alternative to mechanical ventilation. It has been particularly effective in avoiding the need for intubation in patients who are in the acute phase of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or heart-failure exacerbation. NIPPV also can be used during weaning to shorten duration of intubation (unless contraindicated).

Use effective weaning strategies to reduce mechanical ventilation days.

Because VAP risk rises 1% to 3% every day the patient remains on mechanical ventilation, effective strategies to promote weaning can indirectly lower the risk. Nurse- or therapist-driven weaning protocols that include daily assessment for readiness to wean lead to shorter mechanical ventilation periods.

Additional emerging strategies coordinate sedation cessation with spontaneous breathing trials and include early mobility and delirium assessment to promote freedom from the ventilator. The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) introduced the evidence-based ABCDE bundle as an organizational approach to coordinating these complex multidisciplinary weaning efforts. ABCDE stands for Awakening and Breathing Coordination, Delirium Monitoring and Management, and Early Mobility.

Avoid nasotracheal intubation.

Nasal obstruction with an endotracheal tube (or feeding tube) can prevent clearing of sinus drainage, leading to hospital-acquired sinusitis and aspiration of contaminated secretions. When possible, avoid nasotracheal intubation.

Potentially effective strategies

Silver-coated endotracheal tubes and kinetic beds aren’t recommended by any organization, but some supporting evidence suggests these strategies may be effective.

Use silver-coated endotracheal tubes.

Soon after intubation, endotracheal-tube surfaces become coated with a bacterial biofilm. Silver-coated tubes provide antibacterial properties and discourage bacterial adherence, leading to delayed colonization and delayed VAP. Expert opinions on silver-coated endotracheal tubes vary, ranging from “suitable for use” to “additional studies are needed” to “generally not recommended.”

Use kinetic beds.

One meta-analysis found that continuous lateral rotation via the kinetic bed led to reduced VAP rates. However, VAP prevention guidelines rarely include this intervention. The kinetic bed remains “generally not recommended” by The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, while the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement states the bed is “not recommended for routine use.” Rationales for not using the bed include lack of positive impact on death rates and ventilation duration; also, this bed isn’t available in some healthcare organizations.

Multifaceted problem, multidirectional solution

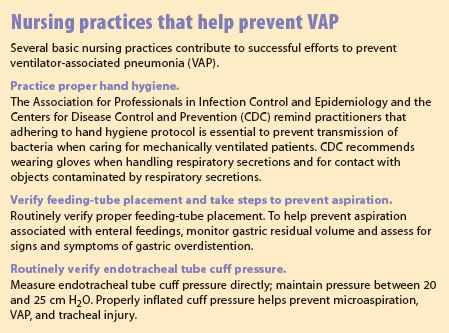

VAP is a multifaceted problem that calls for a multidirectional solution. Successful VAP prevention strategies require interdisciplinary cooperation, education, and monitoring of guideline adherence. The complexity of prevention interventions can make protocol compliance challenging; healthcare facilities may want to group small sets of evidence-based interventions together for easier implementation. Bundling interventions has been shown to promote changes in healthcare professionals’ practices while providing a useful framework for measuring and reporting compliance. (See Nursing practices that help prevent VAP.)

For resources on implementing VAP prevention and ventilator weaning strategies, visit the AACN website (www.aacn.org).

References

Aboelela SW, Stone PW, Larson EL. Effectiveness of bundled behavioural interventions to control healthcare-associated infections: a systematic review of the literature. J Hosp Infect. 2007;66(2):101-8.

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Implementing the ABCDE bundle at the bedside. 2010. www.aacn.org/wd/practice/content/actionpak/withlinks-ABCDE-ToolKit.content?menu=practice

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Oral care for patients at risk for ventilator-associated pneumonia. 2010. www.aacn.org/wd/practice/content/oral-care-practice-alert.pcms?menu=practice

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Ventilator-associated pneumonia. 2008. www.aacn.org/wd/practice/content/vap-practice-alert.pcms?menu=practice

Balas MC, Vasilevskis EE, Olsen KM, et al. Effectiveness and safety of the awakening and breathing coordination, delirium monitoring/management, and early exercise/mobility bundle. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1024-36.

Burns SM. AACN Essentials of Critical Care Nursing. 3rd edition. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2014.

Delaney A, Gray H, Laupland KB, Zuege DJ. Kinetic bed therapy to prevent nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10(3):R70.

Dickenson S, Zalewski CA. Oral care during mechanical ventilation: critical for VAP prevention. Society of Critical Care Medicine; 2008. www.sccm.org/Communications/Critical-Connections/Archives/Pages/Oral-Care-During-Mechanical-Ventilation—Critical-for-VAP-Prevention.aspx

Dudek MA, Weiner LM, Allen-Bridson K, et al. National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) report, data summary for 2012, device-associated module. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(12):1148-66.

Haas CF, Eakin RM, Konkle MA, Blank R. Endotracheal tubes: old and new. Respir Care. 2014;59(6):933-52.

How-to guide: Prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2012. www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/HowtoGuidePreventVAP.aspx

Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Healthcare protocol: Prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. 5th ed. November 2011. www.icsi.org/_asset/y24ruh/VAP.pdf

Jones DJ, Munro CL, Grap MJ. Natural history of dental plaque accumulation in mechanically ventilated adults: a descriptive correlational study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2011;27(6):299-304.

Klompas M, Branson R, Eichenwald EC, et al. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Inf Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35 Suppl 2:S133-54.

Klompas M, Speck K, Howell MD, Greene LR, Berenholtz SM. Reappraisal of routine oral care with chlorhexidine gluconate for patients receiving mechanical ventilation: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):751-61.

Kollef M. Preventive strategies in VAP: focus on silver-coated endotracheal tubes. In: Moriarty TF, Zaat SAJ, Busscher HJ. Biomaterials Associated Infection. New York, NY: Springer; 2013: 531-5.

MacIntyre NR, Cook DJ, Ely EW, et al; American Collecge of Chest Physicians; American Association for Respiratory Care; American College of Critical Care Medicine. Evidence-based guidelines for weaning and discontinuing ventilatory support; a collective task force facilitated by the American Collecge of Chest Physicians; the American Association for Respiratory Care; and the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 2001;120(6 Suppl), 375S-95S.

Perrie H, Windsor S, Scribante J. Nurses’ accuracy in estimating backrest elevation. S Afr J Crit Care. 2007;23(1):10-4.

Rebmann T, Greene LR. Preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia: an executive summary of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, Inc, Elimination Guide. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(8):647-9.

Tablan OC, Anderson LJ, Besser R, Bridges C, Hajjeh R; CDC; Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guidelines for preventing health-care–associated pneumonia, 2003: recommendations of CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004;53(RR-3):1-36.

Torres A, Serra-Batlles J, Ros E, et al. Pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents in patients receiving mechanical ventilation: the effect of body position. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(7):540-3.

Amy Shay is an assistant professor of clinical at the University of Cincinnati College of Nursing in Cincinnati, Ohio, and is on the nursing staff at Miami Valley Hospital in Dayton, Ohio.