Imagine you are talking, and then suddenly you can’t. Your ability to communicate has paused. Over time, or in an instant, your ability to communicate and life as you know it has changed. These communication problems are the result of a neurological disorder known as aphasia, which occurs when your brain’s language center is damaged.

Aphasia is an acquired disorder. It’s a condition, not a disease. Aphasia does not affect intelligence. It occurs in all nationalities, races, sexes, and every age group, though the incidence of asphasia increases with age.

Approximately 1 million individuals suffer from aphasia in the United States, according to the National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Nearly 180,000 Americans acquire the disorder each year.

What is aphasia?

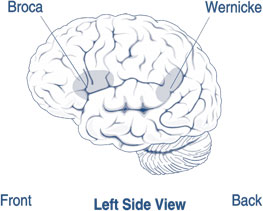

Aphasia is an impairment to parts of the brain affecting the ability to process language and communicate. (See The brain and aphasia.) Aphasia can cause difficulties speaking, listening, reading, and writing. For most people, these are areas on the left hemisphere of the brain. Aphasia usually occurs suddenly, often as the result of stroke or head injury, but it can also develop slowly, as occurs with a brain tumor, infection, or dementia.

Causes of aphasia

Aphasia can be caused by any disease or trauma that damages the parts of the brain that control language:

- stroke

- traumatic brain injuries

- brain tumors

- hemorrhage

- cerebral palsy

- muscular dystrophy

- epilepsy

- surgery

- encephalitis

- Parkinson’s disease

- Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias

Stroke is the most frequent cause of aphasia: 25% to 40% of stroke survivors acquire aphasia, according to the National Aphasia Association. Traumatic brain injuries are another cause of aphasia. A million and a half traumatic brain injuries occur each year in the United States, a figure that does not include such injuries among members of the military. The number of Traumatic brain injuries among military personnel from the year 2000 through the second quarter of 2015 is 333,169. More than 80% of these injuries occur in nondeployed events. The Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center identifies traumatic brain injury as concussion/mild, moderate, severe, penetrating or open /penetrated head injury and not classifiable.

Young adults, particularly males, and children incur traumatic brain injuries from bicycle, motorcycle, firearm, and auto accidents and are at risk for postinjury complications and disabilities including aphasia. In the elderly, falls are the leading cause of traumatic brain injury; posttraumatic dementia, other types of dementia, movement disorders, and Parkinson’s disease may also cause aphasia. As Baby Boomers age, the number of people with all of these diseases and condition are expected to increase, along with the incidence of aphasia.

Types of aphasia

There are many types of aphasia ranging in degree of severity. Anomic aphasia is less severe, primarily involving a struggle to use the correct name for objects, places, or events. In contrast, global aphasia is a severe deficit, allowing little or no ability to speak, understand speech, read, or write; it is often the result of a right hemisphere infarction, tumor, stroke, or dementia. The more common types of aphasia are nonfluent (Broca’s) aphasia and fluent (Wernicke’s) aphasia.

Broca’s aphasia is also referred to as expressive, anterior, and motor aphasia. Damage is usually found in the anterior portion of the left hemisphere, where verbal expression is controlled in the Broca’s area of the frontal lobe. Damage and individual impairments manifest as difficulty in word searching and retrieval to complete sentences. Affected individuals know what they want to say, but have trouble saying it or writing what they mean. Words may be omitted, put in the wrong order, poorly articulated, and inadequate to communicate a clear message. Broca’s aphasia also inhibits the ability to communicate in writing, known as agraphia and dysgraphia, resulting in tremendous frustration and unhappiness.

Remember that an individual with Broca’s aphasia may still understand you, the speaker. Assess their hearing ability. Be aware of the intonation and loudness of your speaking voice. Use simple sentences, not complex ones. Recall that the intellect does not vanish in patients with aphasia. There may be measured understanding of spoken and written language.

Wernicke’s aphasia is known as receptive, posterior, and sensory aphasia. Embolic strokes are often associated with this deficit. The affected area of the brain is in the posterior portion of the dominant hemisphere, which is the left hemisphere in most (right-handed) people. The Wernicke’s area within the temporal lobe integrates comprehension of visual, auditory, and somatic understanding. The individual may not recognize speaking or writing errors and there is poor reading comprehension; they can hear the voice or see the print, but cannot make sense of the words. The resulting dysfunction is marked by what is referred to as “word salad,” putting together unrelated words to complete sentences. The words together lack meaning and are jumbled.

In each type of aphasia, it’s important to remember that the inability to communicate often leads to frustration and depression. (See Aphasia and depression.)

Aphasia and depressionAphasia changes lives, altering self-image; personal, business, and social relationships; and negatively affects the ability to perform activities of daily living, self-confidence, and independence. Thompson and McKeever state that aphasia results in “loss of self,” leading to depression. Symptoms of depression present as reduced appetite and disturbed sleep, sadness, edginess or inner tension, a reduced interest in activities, the inability to feel pleasure, pessimism, and a feeling life is not worth living—even suicidal ideation.Data concerning the full scope of aphasia-related depression are limited because of difficulties with follow-up in health and community settings over time. Persons who are severely aphasic following a stroke and traumatic brain injury are generally excluded from studies of depression; however, there is a great deal of interest globally in postaphasia depression research and best practices to address and treat it. Psychiatrists and therapists can administer developed questionnaires and scales to measure symptoms of depression and how well treatment is advancing.Treatment for poststroke depression includes cognitive behavioral therapy, antidepressants, music therapy, aromatherapy, physical exercise, guided imagery, and family and stroke support groups. A comprehensive assessment of the individual before and the deficit after the stroke is essential for designing a patient-centered post stroke treatment plan. Be mindful that analgesics, narcotics, antihypertensives, amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, digoxin, steroids, antiparkinsonian agents, and sulfonamides may contribute to depressive symptoms. |

Nursing considerations

The importance of your raised awareness of aphasia, its causes, and resulting disorders cannot be understated and are the platform upon which to build an excellent nurse-patient relationship that fosters recovery. Building patient trust begins with compassionate caring. Begin by thinking what your own reaction would be to an inability to communicate. Consider the impact of aphasia on your daily life and on those around you: Would aphasia alter your sense of identity, your self-image, your independence, and your role in life? Consider the loss of the ability to interact fully with friends and family. Could you overcome the associated health risks of feeling and being alone and socially isolated? Pause for a moment and visualize yourself as a patient with aphasia. Each of us can potentially be among those likely to experience an acquired aphasia.

Relating to and engaging the patient with aphasia is essential to providing good care. Patient-centered care and good coordination of that care help determine the patient’s level of satisfaction and encourage a positive outcome.

Communication

The patient’s first impression of you is vital. Skillful communication techniques can shape and contribute to patient satisfaction. Give a great deal of thought ahead of time to the clarity of the message you are providing to the patient. Offer culturally appropriate eye contact to communicate a sense of respect and sincerity in the first meeting, and extend a proper salutation.

The use of patient communication boards that use pictures to communicate engages the patient. The boards enable patients to visually identify and select photos that indicate, “I want, I am.” Other boards can facilitate the want and need for food, people, places and things, toileting, and questions of “when” and “where.” Pain boards offer diagrams to convey the location, type, and intensity of pain.

Know the patient

The need to know and utilize information about the individual patient is essential and empowering. (See Get to know the patient: A checklist.)

Get to know the patient: A checklist

|

The patient’s support system—family and friends—is an important element to consider. Are family members local or are they in other cities and states? Does the patient have an advanced healthcare directive? Are communications with a family member in another state authorized?

Recognize the influences of age, ethnicity, culture, religion, spiritual beliefs, personal circumstances, and the healthcare setting itself on the individual patient.

Keep the focus on the patient. What are his or her concerns and expectations? If the patient can speak, be patient and listen closely; if the patient can write words, read, restate, and clarify what’s written to ensure it is a correct reflection. Offer your full attention, understanding that the words chosen or left out can influence the message. Remember that if the patient speaks a foreign language or has an accent, this will influence your understanding of what is being said.

Build trust, support

Nurse rounding once an hour or every two hours is optimal. The patient may not be able to manipulate the call light or use a verbal appeal for assistance. Whatever the time frame, checking on the patient frequently builds their trust in you.

Collaboration with the rehabilitation team is essential to support the patient. Be aware of the speech-language-therapy plan of care. Offer feedback and documentation to support the patient’s response and progress. A continuum of patient-centered care is achieved through shared collaboration with Social Services and Integrated Care Management.

Resources for patients

Many Internet-based therapeutic resources are available for patients with aphasia and brain injury. There are websites and software that provide communication, memory, attention, speech, and cognitive tools; language and cognitive applications designed for rebuilding speech and memory skills after a stroke or traumatic brain injury; and science-based mobile solutions. (See Selected online therapeutic resources.) Additional aphasia resources can be found on Twitter, You Tube, Facebook, Pinterest, and LinkedIn.

| Selected online therapeutic resourcesConstant Therapy: https://constanttherapy.com.Parrot Software: www.parrotsoftware.com.TalkPath Therapy: https://therapy.aphasia.com/users/landing. |

It starts with you

In your own nursing practice caring for patients with aphasia, work with colleagues. Sharing observations, information, and interactions with others in the care team will help patients. Consider all the information and interventions that help you support improved patient outcomes. A healthcare challenge is ahead, as our population lives longer and is more vulnerable to the conditions that can cause aphasia. Advocate, speak up, and make a difference to persons with acquired aphasia. Build on the sincerity of the nurse-patient relationship. Improved outcomes and patient satisfaction begins with you.

Selected references

Adeoye O, Albright KC, Carr BG, et al. Geographic access to acute stroke care in the United States. Stroke. 2014;45:3019-1024.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Depression after brain injury. A guide for patients and their caregivers. April 2011. http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/77/647/TBI-Depression_ConsumerGuide_04-13-2011.pdf.

Alzheimer’s Association. Frontotemporal dementia. www.alz.org/dementia/fronto-temporal-dementia-ftd-symptoms.asp.

American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke and aphasia. www.strokeassociation.org/STROKEORG/LifeAfterStroke/RegainingIndependence/CommunicationChallenges/Stroke-and-Aphasia_UCM_462875_SubHomePage.jsp.

American Speech Language Hearing Association. Aphasia. www.asha.org/PRPSpecificTopic.aspx?folderid=8589934663§ion=Causes.

Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center. http://dvbic.dcoe.mil/dod-worldwide-numbers-tbi.

Gray RJ, Myint PK, Elender F, et al. A Depression Recognition and Treatment package for families living with Stroke (DepReT-Stroke): Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2011;12:105.

The Joint Commission. Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care: A roadmap for hospitals. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2010.

Lewis SL, Dirksen SR, Heitkemper MM, Bucher L. Medical-Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Clinical Problems. 9th ed. St. Louis, MO; Elsevier Mosby; 2014.

Meiner SE. Gerontologic Nursing. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2011:564-595.

National Aphasia Association. Definitions of aphasia. www.aphasia.org/aphasia-definitions.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Aphasia. www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/aphasia/aphasia.htm.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Traumatic brain injury. www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/tbi/detail_tbi.htm#266693218.

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Aphasia. www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/voice/pages/aphasia.aspx.

Ovbiagele B, Goldstein LB, Higashida RT, et al. Forecasting the future of stroke in the United States: A policy statement from the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:2361-2375.

Poslawsky IE, Schuurmans MJ, Lindeman E, Hafsteinsdóttir TB. A systematic review of nursing rehabilitation of stroke patients with aphasia. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:17-32.

Thompson J, McKeever M. The impact of stroke aphasia on health and well-being and appropriate nursing interventions: An exploration using the Theory of Human Scale Development. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:410-420.

Touchy TA, Jett KF. Gerontological Nursing & Healthy Aging. St. Louis, MO; Elsevier Mosby; 2014: 196-232.

University of San Francisco Memory and Aging Center. Brain 101: Topics in neuroscience. http://memory.ucsf.edu/brain/language/disorders.

US National Library of Medicine. Medline Plus. Communicating with someone with aphasia. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/patientinstructions/000024.htm.

Karen Flaster is president of K Flaster Consulting LLC, in Tarzana, CA, and former executive vice president and chief operating officer of HRN Services Inc., in Glendale, CA.