Nurses can take the lead in preventing harm related to heparin administration.

Takeaways

- Parenteral anticoagulants require appropriate patient teaching to enhance adherence to medication administration.

- Use of unfractionated heparin/low-molecular weight heparins prevent adverse effects from events that cause decreased patient mobility.

- Anticoagulants are the primary treatment in drug management of venous thromboembolism.

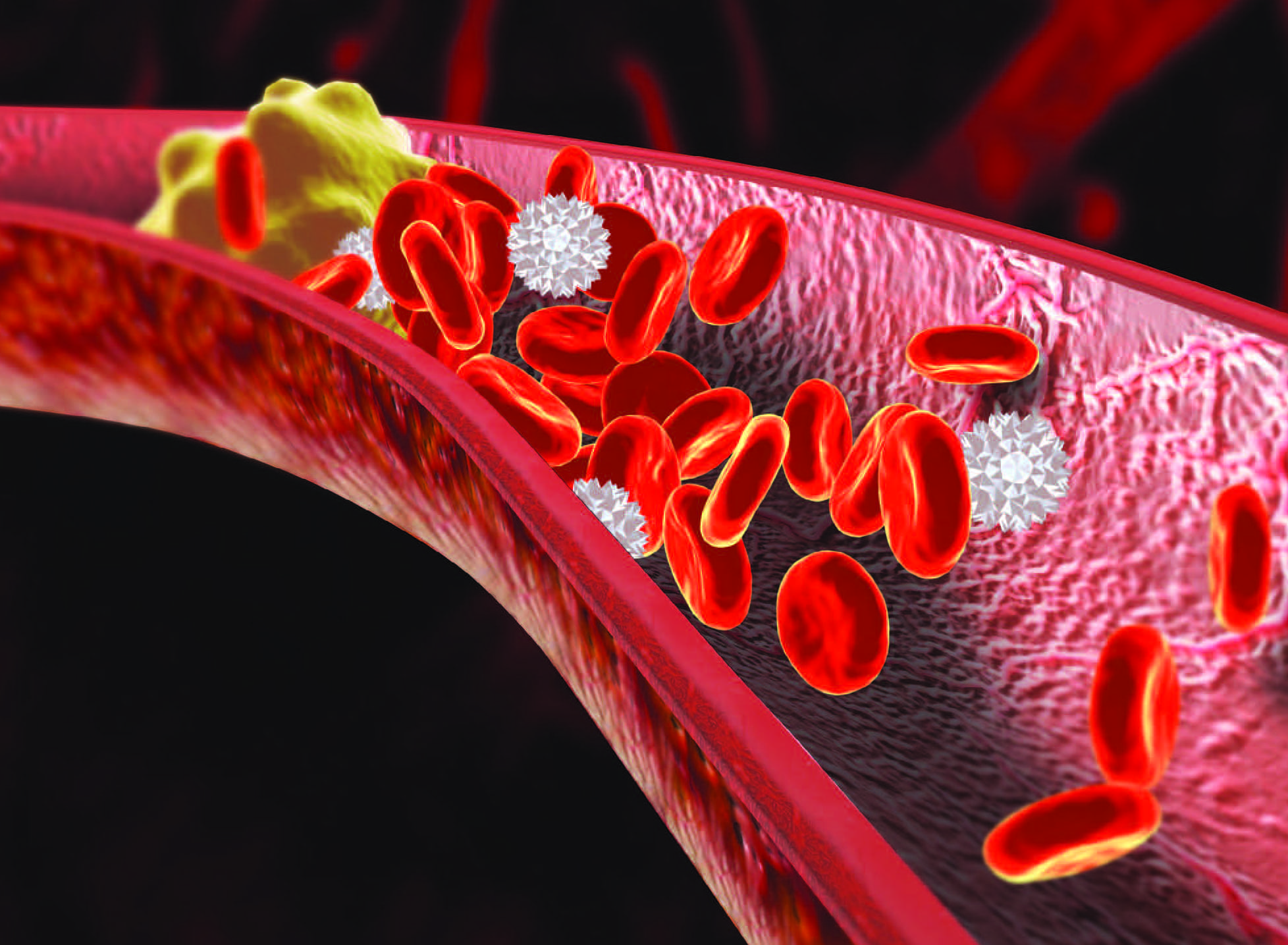

Editor’s note: Anticoagulants remain a mainstay in the pharmacologic management of venous thromboembolism (VTE). In June 2019, American Nurse Journal published “Oral anticoagulants: Pharmacologic management update” (myamericannurse.com/oral-anticoagulants-pharmacologic-update), which includes a description of hemostasis and the clotting cascade. Here the author of that article turns her attention to parenteral anticoagulants.

Parenteral anticoagulants—unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin—primarily are used to prevent and treat VTE (deep vein thrombosis [DVT] and pulmonary embolism [PE]) associated with medical conditions such as atrial fibrillation, heart disease, and atherosclerosis; they’re also used to prevent clotting during dialysis and extracorporeal circulation. The Joint Commission considers heparin a high-alert drug that can result in significant harm, so nurses should understand the differences between the two types of heparin, be aware of potential complications, and provide appropriate patient care and education.

Unfractionated heparin

Unfractionated heparin (UFH) is a rapid-acting, parenteral anticoagulant that suppresses coagulation by binding with the plasma protein antithrombin III to

enhance its inhibitory activity against coagulation factors IIa (thrombin), Xa, XIIa, and IXa. Without these factors, fibrin formation decreases and blood can’t form an adequate clot. The heparin/antithrombin complex forms quickly, and the effects are observed within minutes when the drug is administered by I.V. Heparin also can be administered by subcutaneous injection, but because of its large molecular size and polarity, it can’t be administered orally.

Pharmacokinetics

When administered intravenously, UFH has a half-life of 1 to 2 hours. In patients with hepatic or renal impairment, the half-life increases and requires dosage adjustments. Because heparin can’t cross membranes, it’s safe to use during pregnancy. UFH (which is metabolized by the liver and excreted by the kidneys) is a nonspecific binder to plasma proteins, so free heparin plasma levels can vary.

Therapeutic uses

In hospitals, UFH is used to treat PE and DVT caused by conditions such as atrial fibrillation. It’s also used during major surgeries, such as pelvic and gynecology oncology surgeries. In addition, heparin can be used to treat disseminated intravascular coagulation (a disorder in which fibrin clots form throughout the vascular system) and as an adjunct therapy after thrombolytic therapy to prevent a clot from reoccurring.

Dosage

UFH is available in multiple concentrations, and the amount and method of administration (I.V. or subcutaneous injection) is treatment specific. Many hospitals have established heparin protocols with specific dosages for each condition treated. These protocols provide a structure for patient care and require dosage adjustments based on results of the patient’s activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) or anti-factor Xa levels.

The aPTT (normal is 30 to 40 seconds) is the most commonly used method for monitoring UFH effects. At therapeutic levels, the patient’s aPTT should be one-and-a-half to two times greater than the patient’s normal. If an aPTT is out of this range, the dosage should be adjusted. The aPTT is measured every 4 to 6 hours until the effective dosage has been established, then once daily.

The anti-factor Xa assay directly measures UFH and its activity. The amount of Xa activity is inversely proportional to heparin activity in the blood. Levels of 0.3 to 0.7 international units/mL are within the therapeutic range.

Adverse effects

The main adverse effects of UFH are bleeding and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). (See HIT: Fast facts.) Bleeding can occur anywhere in the body and may be fatal. Excessive bleeding can be treated with protamine sulfate, which neutralizes heparin immediately and lasts for up to 3 hours. When required, protamine should be administered via slow I.V. push at a maximum rate of 20 mg/min or 50 mg in 10 minutes; 1 mg of protamine can reverse the effects of 100 units of heparin.

Other adverse effects include injection site irritation, hematoma, anemia, osteoporosis (with long-term administration), alopecia, and priapism.

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) occurs in 1% to 5% of patients receiving heparin and is more common in surgical patients who have had long-term (10 to 14 days) postoperative thromboprophylaxis or coronary artery bypass and/or valve replacement surgery.

- Type 1 HIT, which typically occurs within the first 2 days of heparin therapy, is a temporary decrease in the platelet count that normalizes as therapy continues.

- Type 2 is an immune-mediated disorder caused by antibodies that develop in response to the heparin-platelet protein complexes. The antibodies cause a decrease in platelets and an increase in clot formation. Type 2 HIT increases clotting across the vascular system and can be fatal.

- Platelet counts should be checked two to three times a week for the first 3 weeks of therapy and then monthly. If the platelet count drops below 100,000/mm3, heparin should be discontinued.

- Because HIT leads to increased clotting and paradoxical thrombus formation, an alternate anticoagulation drug is essential to decrease excessive clotting. Argatroban and bivalirudin can be used to treat HIT.

Contraindications

UFH shouldn’t be used in patients with thrombocytopenia or uncontrolled bleeding, or in those undergoing spinal cord, brain, or eye surgery. Extreme caution should be used in patients with hemophilia, peptic ulcers, dissecting aneurysm, severe hypertension, increased capillary permeability, threatened abortion, or severe liver or kidney disease. In these cases, clinicians should carefully evaluate risks and benefits. If the decision is to administer UFH, the patient should be closely monitored.

Low-molecular-weight heparin

Two low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs) are available in the United States: enoxaparin and dalteparin. Enoxaparin is the most widely used. Similar to UFH, LMWH blocks factor Xa, but it’s less effective at inactivating thrombin; unlike UFH, LMWH doesn’t require regular laboratory monitoring.

Pharmacokinetics

LMWH is metabolized in the liver and excreted by the kidneys, but its longer half-life and its ability to bind with specific plasma proteins makes its action more predictable than UFH. Although LMWH molecules are smaller than those in UFH, they’re very polar, so LMWH can be used during pregnancy.

Therapeutic uses

LMWHs are used to prevent DVT after abdominal, hip, and knee surgery, and to prevent ischemic complications from unstable angina in patients experiencing a myocardial infarction or acute coronary syndrome. Enoxaparin can be given when a patient must be removed from warfarin but still requires an anticoagulant.

Dosage

Enoxaparin is prescribed in milligrams or milligrams per kilogram based on the patient’s weight; dalteparin is prescribed in units per kilogram. LMWH amount and frequency are treatment specific; routine laboratory monitoring is not required. If a patient experiences bleeding, LMWHs can be measured using three tests: aPTT, thrombin generation assay, and antifactor Xa (anti-FXa) assay.

Adverse effects

The incidence of bleeding with LMWHs is less than with UFH. However, HIT can occur, requiring the same interventions as for a patient receiving UFH. Excessive bleeding can be treated with protamine sulfate. The standard dose is 1 mg of protamine sulfate to neutralize 100 mg of enoxaparin or dalteparin.

Other adverse effects of LMWHs include bleeding, injection site irritation, hematoma, anemia, thrombocytopenia, osteoporosis with long-term administration, alopecia, and priapism.

Contraindications

LMWH contraindications include patients with thrombocytopenia and uncontrolled bleeding. All LMWHs have a black-box warning regarding use with patients who receive spinal or epidural anesthesia or a spinal puncture. The drugs can increase bleeding risk that may result in severe neurologic injury, including paralysis. Patients who’ve experienced HIT should not be prescribed LMWHs.

Nursing considerations

Heparin is a high-risk drug, and one of The Joint Commission’s 2020 National Patient Safety Goals is reducing the likelihood of patient harm associated with anticoagulant therapy. (See Error prevention.) Achieving that goal relies on nurses monitoring patients and providing appropriate education. It also relies on patients understanding the importance of treatment and adhering to follow-up appointments and self-injection instructions.

Organizations should implement these steps to prevent heparin administration errors:

- Establish an interprofessional team that includes pharmacists to develop and regularly review policies and protocols for prescribing, administering, and monitoring patients receiving heparin.

- Standardize dosage guidelines and laboratory monitoring and incorporate alerts into the electronic health record.

- Do not allow interruptions when preparing drugs.

- Use smart pumps to infuse I.V. heparin.

- Track and conduct a root cause analysis of errors and near misses to determine areas for improvement.

- Provide predischarge patient education (including return demonstration) on self-administration and monitoring.

- Use two RNs for order and dosage checks.

Nurse responsibilities

To reduce the risks associated with heparin therapy, nurses must:

- monitor laboratory results and assess for bleeding

- provide oral and written instructions for patients (be sure instructions are in the patient’s preferred language and that the print size is large enough for those with visual impairment)

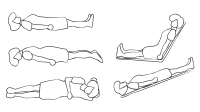

- ask the patient to perform a return drug administration demonstration, including:

- changing the needle before subcutaneous administration after withdrawing the medication from the vial

- using appropriate injection sites such as the stomach or abdominal fat layer (avoiding areas within 2 inches of scar tissue or the umbilicus) or on the front and sides of the upper thigh

- withdrawing the needle quickly and applying gentle pressure to the site after injection, but not massaging or applying heat or cold.

Patient responsibilities

As part of patient education, instruct patients to:

- attend follow-up monitoring appointments as required

- understand the importance of taking the drug as prescribed and what to do if a dose is missed

- store the drug at room temperature

- check the drug’s expiration date before administering each dose

- rotate injection sites using a supplied diagram showing acceptable sites and to keep a record so they don’t forget the pattern

- wash their hands before drug administration

- dispose of needles and syringes in a puncture-proof container with a lid; when the container is full, they should dispose of it properly as required by their state or county

- watch for increased incidence of bruising, black or tarry stools, and increased incidence of nosebleeds, which may indicate that bleeding time has increased

- be aware of lifestyle changes that can help reduce bleeding risk, including:

- shave with an electric razor

- use a soft-bristle toothbrush and waxed floss

- wear cut-resistant gloves when using knives, and keep knives sharpened to reduce slippage

- avoid activities and behaviors (playing contact sports, increased alcohol consumption) that may lead to falling or self-injury

- remove or rearrange items (furniture, area rugs) in the home that may pose an injury or fall risk

- wear a helmet when bike riding.

- wear a medical alert bracelet.

- contact a healthcare provider before taking any newly prescribed or over-the-counter drugs, vitamins, or herbal supplements. (See Drug-to-drug interactions.)

Patients receiving heparin therapy (unfractionated heparin [UFH] or low-molecular-weight heparin [LMWH]) should avoid any drugs that depress platelet function or affect anticoagulation, such as aspirin, naproxen, and clopidogrel. Obtaining a thorough history will help uncover whether patients are taking any herbal supplements that may increase the risk of bleeding. Instruct patients to avoid these supplements for the duration of heparin therapy.

Patients receiving UFH shouldn’t take:

- dong quai • ginger

- evening primrose • ginkgo biloba

- fenugreek • red clover

- garlic

Patients receiving LMWH shouldn’t take:

- fish oil • ginkgo biloba

- garlic • ginseng

- ginger

Promote positive outcomes

Heparin can be a lifesaving drug, but it comes with serious adverse effects that can be life-threatening. When nurses are alert to potential complications and provide thorough patient education, they can promote positive outcomes

Nancy Haugen is associate dean, prelicensure and undergraduate programs, at the Samuel Merritt University School of Nursing in Oakland, California.

References:

American Society of Hematology. ASH VTE guidelines: Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). 2018. hematology.org/Clinicians/Guidelines-Quality/VTE/9180.aspx

Burchum J, Rosenthal L. Anticoagulant, antiplatelet, and thrombolytic drugs. In: Lehne’s Pharmacology for Nursing Care. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018: 604-32.

Eke S, May SK. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Medscape. April 24, 2018. emedicine.medscape.com/article/1357846-overview#a6

Gray E, Hogwood J, Mulloy B. The anticoagulant and antithrombotic mechanisms of heparin. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2012;207:43-61.

Joint Commission, The. National Patient Safety Goals Effective January 2020: Hospital Accreditation Program. jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/NPSG_Chapter_HAP_Jan2020.pdf

Joint Commission, The. R3 Report Issue 19: National Patient Safety Goal for Anticoagulant Therapy. December 7, 2018. jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/R3_19_Anticoagulant_therapy_Rev_FINAL1.PDF

Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelis J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-52.

RN.com. Understanding the hazards of heparin. May 2018. lms.rn.com/getpdf.php/2247.pdf?Main_Session=15a98fee0cac6fcb06ebc9a809988209

Schurr JW, Stevens CA, Bane A, et al. Description and evaluation of the implementation of a weight-based nurse-driven heparin nomogram in a tertiary academic medical center. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2018;24(2):248-53.

Skidmore-Roth L. (2020). Mosby’s 2020 Nursing Drug Reference. 33rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020.