Establish a culture of patient safety.

- The number of patients seen in urgent care clinics can present unique medication administration challenges.

- Reducing errors requires a culture of patient safety, which includes staff and patient education, strong medication administration policies, and proper labeling and storage.

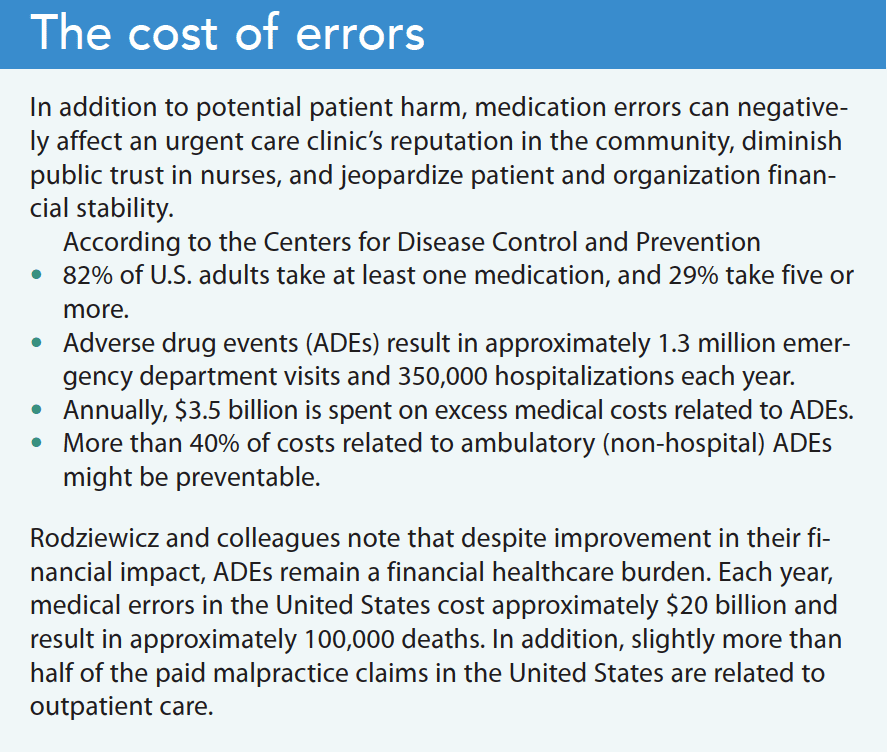

Medication errors can occur in any setting. They endanger patients, can lead to costly litigation, and may damage the reputations of providers, nurses, and organizations. The number of patients seen in urgent care clinics (UCCs) can present unique medication administration challenges. Reducing medication errors in UCCs requires a culture of patient safety, which includes staff and patient education, strong medication administration policies, and proper labeling and storage. (See The cost of errors.)

Alligators, swamps, and medication safety

The nurse’s role in medication safety

Mindfulness for medication safety

Patient safety culture

Farokhzadian and colleagues define the culture of patient safety as individual and group values, beliefs, attitudes, procedures, and competencies combined with nurses and management patterns of behavior that determine the commitment of a clinical organization toward overall patient well-being. Nurses and management must demonstrate ongoing teamwork toward the common goal of minimizing adverse drug events (ADEs). Ongoing education, including evidence-based guidelines can help support this goal. Frameworks that support a culture of safety include the five rights of medication administration, personal reflection, and the Donabedian Quality of Care Model.

The traditional five rights of medication administration (right patient, right drug, right route, right time, and right dose) have long been relied on to minimize medication errors; however, some studies have considered additional rights, including right documentation. When combined with personal reflection, this cornerstone of nursing practice can help reduce errors.

Ongoing personal reflection enhances a nurse’s ability to transform what they know and what they’ve learned into a higher understanding of the nursing process, which guides clinical decision making and impacts best practice and clinical outcomes. Galutira noted that, as a lifelong process, learning allows individuals to find meaning in their lived experiences.

Sherwood notes that developing a culture of patient safety requires nurses to identify and alleviate clinical conditions and processes that contribute to preventable harm. For example, the Donabedian Quality of Care Model describes how an organization’s structure and processes can impact patient care. (See Quality of care model.)

Structure

The increase in patients using UCCs also increases the risk of medication errors occurring in these settings. UCC nurses can minimize errors and improve outcomes by using the existing wealth of evidence-based practice research about medication safety in the hospital setting. Nurses in UCCs retain responsibility for ensuring they administer correct medications ordered by providers. They should draw on their knowledge base and past experiences (including adverse outcomes) and ask for clarification of orders with which they’re not familiar, have limited knowledge, or believe may be incorrect (such as dosage or route).

Example: Thomas Daley* arrives at the UCC with generalized muscle pain. The provider examines Mr. Daley and orders a 30 mg intramuscular injection of ketorolac and a 5-day course of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Relying on her education, past experiences, and structural processes, the nurse advises the provider of a possible interaction with warfarin, which Mr. Daley takes daily. This application of self-reflection and the Quality of Care Model reduces the potential for an ADE and enhances patient satisfaction, outcomes, and quality of life.

UCC management can aid error reduction by establishing a nonpunitive approach to error reporting. Mutair and colleagues acknowledge the importance of minimizing medication errors, but note that management must create an atmosphere where nurses and other staff members aren’t afraid to speak up when errors or near-misses occur. When staff don’t disclose medication errors out of fear of punishment, the organization can’t fulfill its goal of an overall culture of safety. Nurses should feel empowered to recognize their mistakes and trust that leadership will guide them through an interprofessional resolution process that includes education to reduce future ADEs.

Process

Nurses help to support a culture of safety by being aware of all the medications (oral and injectable) provided in the UCC, why they’re used, and how to administer them. In addition, nurses should take an active role in safe medication storage.

Medication safety begins when the patient arrives at the UCC. Nurses must focus on gathering information about current medications, including over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, vitamins, and supplements. Many patients view OTC medications as harmless, but nurses can use this educational opportunity to ensure that medications and supplements are understood in context, that they don’t pose a serious health risk, and to uncover potential medication interactions.

Safe storage includes placement to avoid confusing look-alike/sound-alike drugs and locks to ensure medication security. Look-alike/sound-alike medications should never be stored next to one another. For example, Rocephin 250 mg for injection shouldn’t be placed next to Rocephin 1 gram. Instead, they should be stored separately in clearly marked bins. Similarly, acetaminophen liquid should be stored on a shelf designated for liquid medications only so that a nurse doesn’t inadvertently pull acetaminophen tablets, which should be placed on a tablets and capsule shelf.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) has designed a hierarchal graph for display in medication rooms. It demonstrates strategies from easiest to most difficult to implement. The graph serves as a reminder to improve medication safety and includes guidelines established by the UCC.

Some drugs—including eye medications, antibiotics, vaccinations, and tuberculin testing products—require refrigeration. Several laboratory controls also require refrigeration. This knowledge can help minimize medication errors and serious patient harm. For example, urine controls come in a dropper bottle similar to tetracaine eye drops. Administering urine controls as eye drops can result in serious complications including loss of sight. Refrigerated controls should never be stored with medications or vaccinations; they should be placed in a separate refrigerator clearly marked for lab use only with a biohazard label.

Vaccination errors commonly occur in the UCC and other outpatient settings. They don’t typically cause serious adverse reactions, but nurses should recognize the potential for error. For example, a provider might order tetanus toxoid (Td) but the nurse inadvertently administers tetanus toxoid diphtheria, and pertussis (TDaP). The patient probably won’t experience any adverse effects, but this remains a medication error. Other examples of mistakes related to look-alike/sound-alike vaccines include hepatitis A adult and pediatric doses and influenza adult, senior, and pediatric doses. Similar to refrigerated medications, vaccines that require refrigeration must be stored at the correct temperature.

Speak up

Nurses should view all medication administration as a potential ADE. With that mindset, they can help minimize medication errors in all settings, including UCCs. Nurses must speak up to ensure ISMP standards and guidelines are part of their daily practice and incorporate self-reflection while using the quality of care model as a guide. These steps can help streamline patient flow, increase the clinical reputation of the UCC, and enhance nurses’ confidence as patient advocates.

*Name is fictitious.

Scott B. Coffey owns and operates Comprehensive Health and Wellness Center in Gallatin, Tennessee, which provides urgent and primary care to patients in the middle Tennessee area.

Key words: urgent care clinics, medication errors, patient safety

American Nurse Journal. 2023; 18(3). Doi: 10.51256/ANJ032322

References

Centers For Disease Control and Prevention. Medication safety basics. September 28, 2010. cdc.gov/medicationsafety/basics.html.

Farokhzadian J, Dehghan Nayeri N, Borhani F. The long way ahead to achieve an effective patient safety culture: Challenges perceived by nurses. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):654. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3467-1

Galutira GD. Theory of reflective practice in nursing. Int J Nurs Sci. 2018;8(3):51-6. doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20180803.02

Hanson A, Haddad LM. Nursing rights of medication administration. StatPearls. September 5, 2022. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560654

Institute for Safe Medication Practices. ISMP list of high-alert medications in community/ambulatory care settings. September 30, 2021. ismp.org/recommendations/high-alert-medications-community-ambulatory-list

LoPorto J. Application of the Donabedian quality-of-care model to New York State direct support professional core competencies: How structure, process, and outcomes impact disability services. J Soc Change. 2019;12(1):40-70. doi:10.5590/JOSC.2020.12.1.05

Mutair AA, Alhumaid S, Shamsan A, et al. The effective strategies to avoid medication errors and improving reporting systems. Medicines (Basel). 2021;8(9):46. doi:10.3390/

medicines8090046

Rodziewicz TL, Houseman B, Hipskind JE. Medical error reduction and prevention. StatPearls. December 4, 2022. bit.ly/40TfIAy

Sherwood G. Quality and safety education for nurses: Making progress in patient safety, learning from COVID-19. Int J Nurs Sci. 2021;8(3):249-51. doi:10.1016/j.ijnss.2021.05.009